The best kind of ambition

There's nothing wrong with being an Olympic skiier, but the best kind of ambition goes off-piste

In grade school, a boy made fun of me for bringing my lunch to school in a milk bag instead of a lunch bag. Kids are dumb and cruel: I can now laugh at the silliness of this, but it mattered at the time. I spent much of my teens and early 20’s being viciously, desperately focused on increasing earning power, simply because I hated not having money and not having things that other kids had.

The funny thing is that the paths by which you can increase earning power in North America (or most developed, free-market Western liberal democracies) look very different from the paths that lead to the creation of cool new things. What many call “business school” would be better described as a finishing school for corporate etiquette. Much as ladies were taught to comport themselves in a way to market themselves as marriageable, business school’s biggest value prop seems to be teaching you how to signal reliability, cooperativeness, an unlikelihood of being disruptive, and a willingness to respect defined paths and take them seriously. All good traits for working within a sensible corporation; all terrible traits if you were to ever find yourself in a post-pandemic social collapse.

If we ever come to a world where government has disintegrated and society has broken down, I think there are 3 kinds of people: the ones who would quickly bite the dust; the ones who would hang on pragmatically but still reminisce about old institutions (à la A Quiet Place); and the ones who would embrace the new chaos without looking back, and find a way to thrive (probably by setting up a black market cartel for clean water, or something of the like).

After spending a week in Bogotá with a friend who I think would fit that third description, I’ve realized just how far I’ve come from that hungry, desperate version of myself. And here I use the word desperate not in any kind of pathetic or pleading sense; I mean desperate as in, I will do any. goddamn. thing. to get to my objective. Resource-constrained people with non-negotiable needs always drum up the most creative of solutions. One of the best lines from Hamilton is “immigrants - we get the job done”: this is due less to some admirable work ethic, and more because you have no other fucking choice.1

When people talk about ambition and success they are usually talking about one of two things: either having made it as far as possible down a path that somebody else constructed for you; or being very effective at doing things that you are not supposed to do, in spaces that you’re not supposed to be in. I suspect a large part of my uncooperative and abrasive2 nature comes as a cope, and an attempt to embrace something that I had no choice in as a kid: I was never going to fit in, no matter how hard I tried - so at some point I stopped trying.

There was of course a large part of me that simply wanted to be middle class and white. I relished being invited to Thanksgiving dinner by friends and significant others. I viewed it as an act of cultural tourism, the way that most Americans would view a tea ceremony in Japan or a tribal dance in Mongolia. Over time I think I had so quietly achieved that objective that I hadn’t even noticed. My WhatsApp contacts list has a serious diversity problem that would make most Fortune 500 boards look woke.

To a certain extent, assimilation is a relief. It’s mentally exhausting to go through life every day being keenly aware of the ways in which you do not fit into other people’s spaces, cultures, and institutions. It’s fun as a tourist for one week; but to have it be an everyday fact of life slowly wears you down. You start to feel as if there is something wrong with you, and that you’ll never be the right thing no matter what you do.

That is why I value the moments where I get to step out of the constructs that I tried so hard to assimilate into. Sometimes this is via mind-altering substances. Most recently it was due to spending a week in a society where all constructs - even police, even the law, even physical fences, even physical safety - are apt to bend or break if it would serve someone’s intended purpose.

In that sense, ambition in the chaos of loose or non-existent social constructs is the most difficult, most honest, and therefore the most admirable form of ambition. It can be compared to conventionally defined professional success as much as you can compare an Olympic downhill skiier carving around flags to someone who crosses a valley off-piste. They are both acts of incredible skill and determination, but there is something more honest about the latter. On an Olympic ski hill you stand to lose a medal; out in the wilderness, you stand to lose your life.

The ambitions that arise out of resource constraints, whether from immigration or from living in a developing country, are of a special nature. They are hungry. They are desperate. Their stakes are real. They are gravely honest in a way that constructed games cannot be. In a developed country, so many of our needs are taken care of and taken for granted that we can’t help but start playing constructed games with great seriousness.

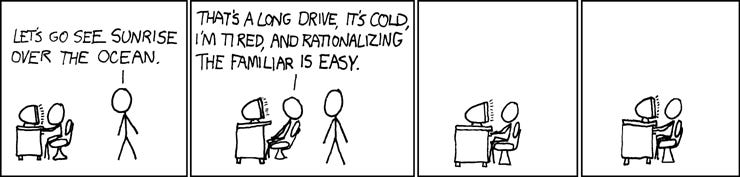

Once such ambition is lost, it’s a hard thing to get back. Comfort is the quietest of killers. It’s easy to rebel against systems; it’s much harder to rebel against your own desire for comfort, ease, pleasure, and security. And I mean really rebel; I don’t mean going to a messy foreign country for a week and jumping off of moving buses just to feel alive for a moment.

I mean genuinely looking out into chaos, and if you deconstruct enough institutions in your mind, chaos is all you will be left with. I recently realized that I am obligated to no one, tied down to no country, and have no particular job that I need to do. Such a state sounds like freedom, and the envy of many who are weighed down by diapers to change, family to consider, mortgages to pay, or pensions to obtain. But the price to pay for such privilege is deeply, deeply humbling if you look at it honestly: it means that there is no person, family, culture, or institution that you can blame for the failures of your life, because your choices are irrefutably and entirely your own.

The most life-affirming kind of ambition, then, is staring honestly into such chaos, feeling terrified, and then saying, “I’m going to build something real”. I have deep admiration for the people who do so, because I know that such a way of living comes at the cost of enormous loneliness, doubt, and pain. It comes at the cost of staring out into the void and wondering if you’ve gotten it all horrifically, utterly wrong, because it feels so weird that there is nobody out in this freezing, snowy part of the mountain with you. It’s a pain that I hope to feel one day - if I’m not feeling it already - because it means that I will be one of those people.

This is essay #49 in my commitment to write one essay per day for 49 days. Now I’m going to….keep going.

Examples: washing dishes, cleaning hotel rooms, and assembling cheap necklaces, even though you have an MD from the best medical school in your former country. This is why during internships or junior roles at work, I have always refused to do things like fetch coffee, take meeting minutes, or pass the microphone around a room. My parents did the bullshit jobs because they had no choice. I do.

Actual adjective that has been used to describe me at work many times.

I found this really moving and honest - and felt a special connection to your description of being "desperate and hungry" in your early adulthood. That sense of ravenous, restless desire is something I've spent the majority of my life being a slave to too, and something that I still grapple with - something a lot of us from immigrant families grapple with.

I also found your distinction between playing "constructed" vs. real games really though provoking - it makes me think of the fact that the more we live in a constructed world, the less human we become. Because we do less and less of the things that make us human. There's a quote, I forget from who - "Love or pain or danger makes you real again". I think when we live in a world that lets us convenience ourselves out of all those things, it's hard to be a real human being.

I wonder if you've read Brene Brown's book "Braving the Wilderness"? It touches on similar themes of "belonging to yourself" and doing the scary, lonely thing that's real. I think you'd find it interesting.