Love you to death

"The Husband Stitch" by Carmen Maria Machado is hailed as a feminist masterpiece. I worry that it's an excruciating account of an abusive relationship

In 2014, a short story called “The Husband Stitch” was nominated for a Nebula Award. It is the most popular story from a collection called Her Body And Other Parties, by Carmen Maria Machado. It is considered a brilliant feminist retelling of a messed up childhood folk tale, which goes like this:

A girl named Jenny wears a green ribbon around her neck. Jenny marries a boy named Alfred, who always asks her about her ribbon, but she doesn’t answer.

Here is the ending, from In a Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories by Alvin Schwartz:

One day Jenny became very sick. The doctor told her she was dying.

Jenny called Alfred to her side.

“Alfred,” she said, “now I can tell you about the green ribbon.

Untie it, and you will see why I could not tell you before.”

Slowly and carefully,

Alfred untied the ribbon,

And Jenny’s head fell off!

I’m not sure what kind of psychopath writes a book like this for children, but it’s downright wholesome compared to Machado’s rewrite. Jenny waits until the end of her life, when she is on her deathbed. Alfred unties the ribbon with great care, and only after Jenny asks him to.

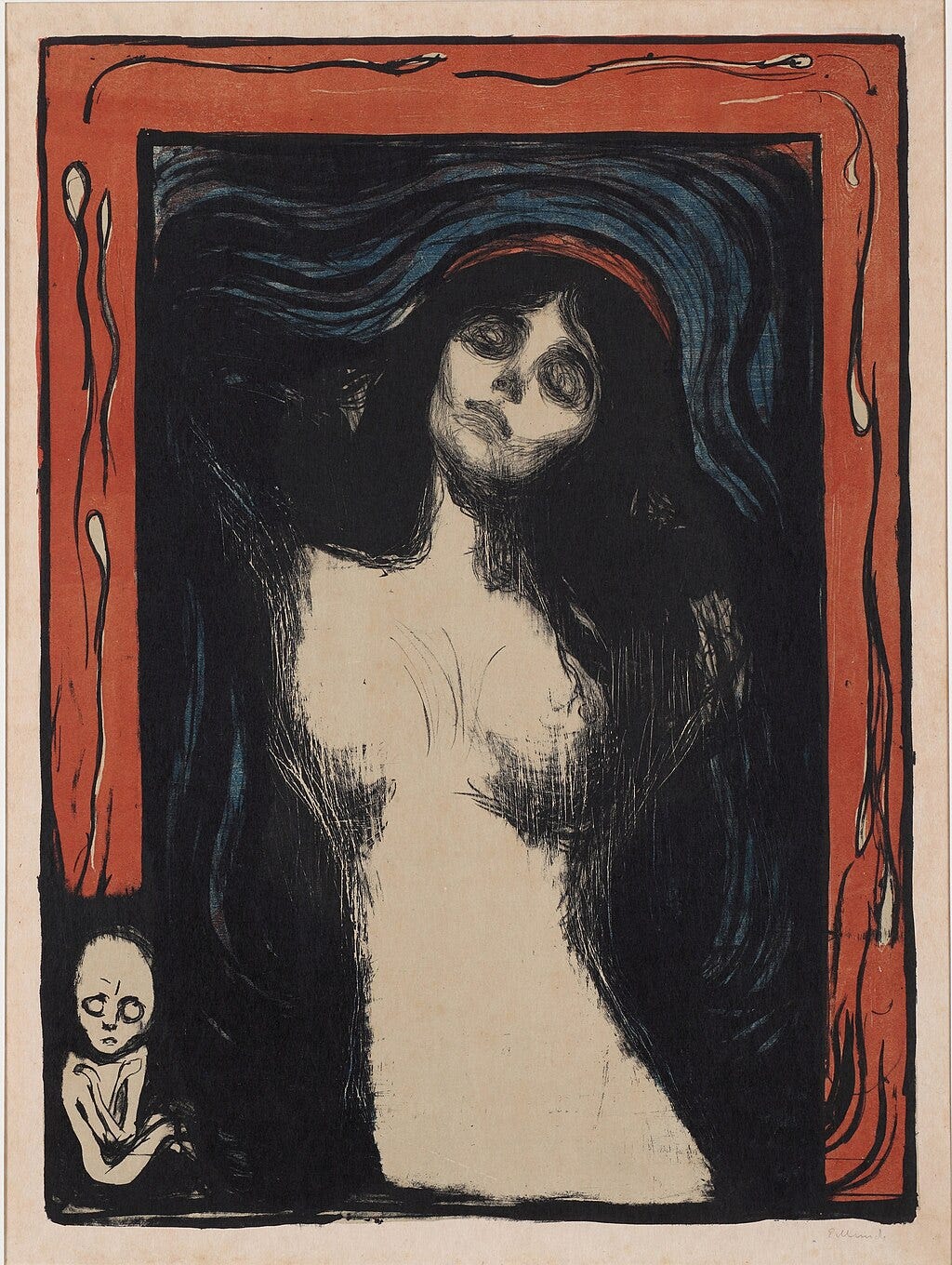

Machado’s version, on the other hand, is the stuff of nightmares - a scathing commentary on consent and the ways in which women’s bodies are treated as objects by a supposedly patriarchal culture. Trauma drips out of it, like some kind of bleeding, dying creature. It will make your stomach churn.

(Spoilers ahead if you wish to read the story yourself. It is brilliantly written, but a tough read.)

Machado’s female protagonist, sexually precocious and not knowing any better, marries her childhood crush and has a baby with him. He turns out to be…a horrific human being:

“Come back here,” he says.

“No,” I say. “You’ll touch my ribbon.”

He stands up and tucks himself into his pants, zipping them up.

“A wife,” he says, “should have no secrets from her husband.”

“I don’t have any secrets,” I tell him.

“The ribbon.”

“The ribbon is not a secret; it’s just mine.”

“Were you born with it? Why your throat? Why is it green?”

I do not answer. He is silent for a long minute. Then, “A wife should have no secrets.”

The story ends in the exact god-forsaken way that you know it will:

Resolve runs out of me. I touch the ribbon. I look at the face of my husband, the beginning and end of his desires all etched there. He is not a bad man, and that, I realize suddenly, is the root of my hurt. He is not a bad man at all. To describe him as evil or wicked or corrupted would do a deep disservice to him. And yet—

“Do you want to untie the ribbon?” I ask him. “After these many years, is that what you want of me?”

His face flashes gaily, and then greedily, and he runs his hand up my bare breast and to my bow. “Yes,” he says. “Yes.”

I won’t quote the entire ending here, but it’s as bad as you imagine:

My husband frowns, and then his face begins to open with some other expression—sorrow, or maybe preemptive loss. My hand flies up in front of me—an involuntary motion, for balance or some other futility—and beyond it his image is gone.

“I love you,” I assure him, “more than you can possibly know.”

I felt deeply disturbed after I read the Machado story, much more so than the original folk tale. Accounts of abuse are difficult to read. Watching a woman forgive, over and over, and profess her unending love for a man who repeatedly disrespects her boundaries is both exasperating and hard to stomach. On the one hand the story makes you want to castrate this sorry excuse of a so-called “husband”; on the other hand, you want to shake the damn woman and ask her why in the world she’s still with him.

The line that truly made me want to scream and throw this book against a wall was the following:

He is not a bad man, and that, I realize suddenly, is the root of my hurt. He is not a bad man at all. To describe him as evil or wicked or corrupted would do a deep disservice to him.

Except the protagonist is…wrong. He is a bad man. He is, at the very least, a terrible, terrible partner. Abuse is abuse: watching someone lie to themselves like this is agonizing. The fact that the story is fictional is sparse comfort, only because such stories are all too common in real life.

Some people might say that I’ve missed the point of the story entirely, which is to recognize that the husband isn’t evil - he’s also a lover, and a provider, and a good father. He’s just a part of the big ol’ dumb patriarchy, which is the true cause of women’s woes. And the poor protagonist, who gave and gave of herself and her love, kept giving until it finally killed her, for such is a woman’s role in society. It’s a storyline that I hate1, and a premise that I find uncomfortable.2

To chalk the husband and the doctor’s behaviour up to patriarchy - to “men being men” - is to forget that they are individuals who are accountable for their actions. This scene in the hospital, in which the husband asks for the titular “husband stitch” after the birth of their child, is especially infuriating:

“How much to get that extra stitch?” he asks. “You offer that, right?”

“Please,” I say to him. But it comes out slurred and twisted and possibly no more than a small moan.

Neither man turns his head toward me. The doctor chuckles. “You aren’t the first—”

One perspective is that I ought to be furious at these men for doing their patriarchal “men” thing and making vile jokes over the body of this poor, enfeebled woman who literally cannot speak. Another perspective is that I ought to to be furious at the husband for being an absolute imbecile, when any husband worth their salt would have given the doctor a black eye for daring to crack a joke like that - let alone cracking it himself. And - perhaps the least kosher perspective to hold - is that I ought to be furious at this woman for marrying and having children with an absolute muppet.

Ultimately, it was my partner who pointed out that I was reading Machado’s story with a lack of empathy. That abusive relationships rarely start out abusive; that they, in fact, usually start out with the sort of raging passion and obsessive adoration that Machado skillfully paints at the start. That leaving isn’t so simple; that beyond practical considerations like finances, or children, that there are other complications: apologies, the hope that things will get better, the hope that things will go back to the way they used to be. A saving grace in Machado’s story is that the husband’s inability to show basic respect doesn’t extend to their child. The son grows up happy, and successful, and loved. (If the kid was also abused, I probably would have thrown the book out of the window in rage.)

An empathetic reading would reveal a thread throughout the story, of an almost-happiness, of a self-deluded hope, of a need to believe that things are ok - good, even:

When he tells us that he has been accepted at a university to study engineering, I am overjoyed. We march through the house, singing songs and laughing. When my husband comes home, he joins in the jubilee, and we drive to a local seafood restaurant. His father tells him, over halibut, “We are so proud of you.” Our son laughs and says that he also wishes to marry his girl. We clasp hands and are even happier. Such a good boy. Such a wonderful life to look forward to.

Even the luckiest woman alive has not seen joy like this.

It is true that the luckiest woman alive has not seen joy like this: Machado’s protagonist lived and died in a tragedy, not a romance. It is a lesson in what not to do.

Let us not mistake the story for an account of what it means to love as a woman. It is precisely the opposite.

Speaking of truly “feminist” texts, the single book that I think has done the most to dismantle the “I can fix him” mindset is Women Who Love Too Much by Robin Norwood.

Call me naive but I think it’s important to question the value of framing things in terms of the “patriarchy”, or most other gender theory constructs. I once went to a dance class that happened to be at a women’s-only studio: the instructor said something about having a space for self-expression that is “not subject to the male gaze”.

The problem, of course, is that I’m not sure any of us were even thinking about “the male gaze” until she mentioned it. By using the framing, the instructor inadvertently invited the idea of “the patriarchy” into a space where we were previously just…enjoying ourselves.