[spoilers within for Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain]

My feelings about the movie Amélie have varied over time. In first year of university, I had the poster on my dorm room wall. I wanted a subtle way to let visitors know that I was a quirky, adorable, misunderstood soul just waiting to be discovered. A few years later, I did what most of us do with love at some point: I threw up my hands and said, fuck this noise - I’d rather die alone than go through this bullshit again.

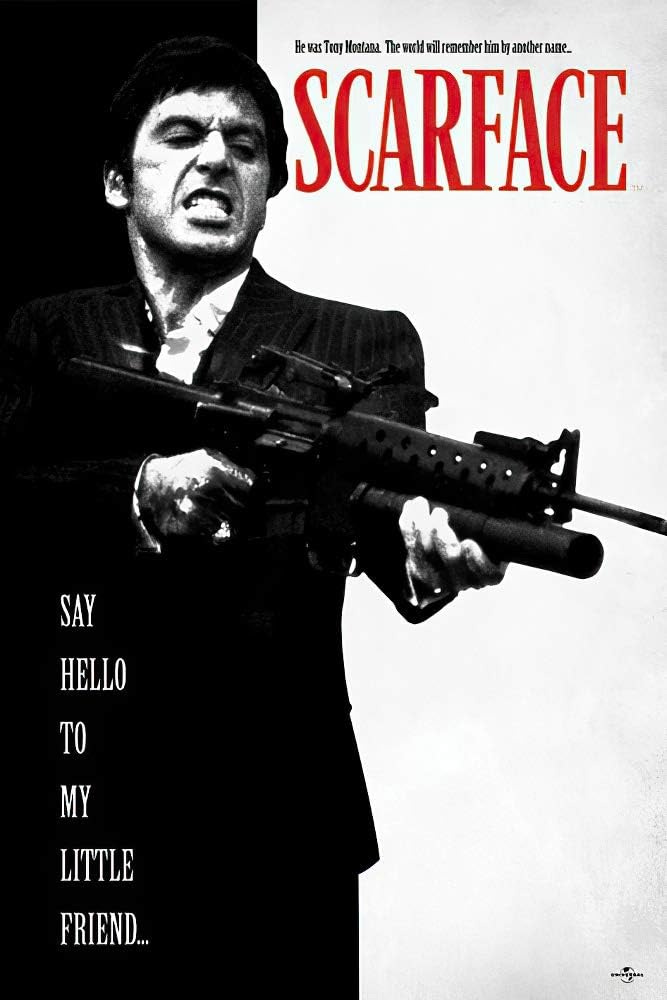

I took the poster down and replaced it with this one:

Directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Amélie is probably the most successful French movie in the English-speaking mainstream. It’s a pillar of the cultural mythology which brings millions of tourist dollars and short-term séjours to France every year. After all, who doesn’t like the idea of LARPing some fanciful, lonely, disaffected soul, absentmindedly skipping your way through the cute little streets of Paris, always being one serendipitous lost item away from finding the love of your life?

I recently rewatched it while staying in a part of town called Porte de Clignancourt. It’s in the 18eme arrondissement, where Montmarte, the home of our movie heroine, is located. Montmartre is where you’ll find Sacre-Coeur, the Café des Deux Moulins (where Amélie is a waitress), and other charming attractions.

Porte de Clignancourt is the very last stop on line 4 of the Paris metro, and it lies considerably north of Montmartre. Depending on which TripAdvisor review you are reading, it’s a part of town that is either solidly gentrifying, or a bloody war zone. A quick look around reveals that the neigbourhood is just fine, if not a little dirty1.

Actually, the strongest driving force behind the area’s poor reputation may just be xenophobia. The population runs along racial lines that make no appearance in Amélie’s Montmartre. Jeunet and his crew apparently removed garbage, graffiti, and traffic from each scene before filming. Amelie’s backdrop is a Paris scrubbed of rough edges - in a sense that may be more than literal.

Amélie is…actually kind of a jerk

If you can pull your attention away from the film’s aesthetic brilliance, gorgeous soundtrack, and endearing quirkiness for just one moment2, you’ll realize that it’s…ridiculous. Amélie is a bit of an asshole. She steals. She lies. She blatantly disrespects personal property and breaks into people’s homes. She forges a fake letter to manipulate Madelene, the building concierge, into thinking that her cheating husband really did love her. The grocer, Collignon, is admittedly a bit of a jerk, so she booby traps his apartment by tampering with his lamp cord. (Never mind that this could go awry and land her a manslaughter charge). She leads Nino on a cryptic goose chase around Paris that most self-respecting men would have bailed on, presumably because they have better things to do than repeatedly chasing after a girl who won’t even introduce herself.

You don’t need to look very hard to find other reasons to call the movie absurd. (Let’s not forget the insane premise that Amélie is able to afford rent within metropolitan Paris on a waitress’s salary). So why the hell do we still like this movie so much?

We know what the opposite looks like, and it’s worse

It’s easy to recognize the negative of Jeunet’s fanciful world, because it looks like ours. It’s a world of mortgages, and racist graffiti, and kids jumping over metro turnstiles as cops wearily look on and do nothing. It’s a world of mind-numbing office jobs, and assholes on Tinder, and marriages that are compromises at best, and life sentences at worst. To live in this world is to fight, constantly, against the gravity of exhaustion and meaningless garbage. It’s a force that pulls you into dead places, and threatens to slowly bury you there.

Romanticism done wrong is simply wish fulfillment without having done any of the work, and that is indeed what happens in this movie. Note that for all the glass man’s encouragement for Amélie to take a risk and get out there, we don’t actually see her doing so. The movie only has a happy ending because Nino shows up at her apartment, literally out of nowhere.3

But haven’t we all hoped for this at some point? I think we like this movie because we all recognize that it’s better to have romantic dreams, however tentatively and cautiously - and maybe one day find the courage to throw them against reality - than to never have those dreams at all. To be on that edge between where we are and the things we really want, and not quite having the courage to jump yet, is honestly where most of us live. And most of us keep hoping - and keep telling ourselves - that we won’t be there forever. In that sense, perhaps Jeunet’s story is more realistic than I thought.

I think the appropriate reaction here is not a cynical derision, as I once felt - but more like what we'd feel towards a child who still believes in Santa. I can deeply empathize with the desire of wanting to get away from the humdrum of it all - taxes, and garbage, and the socioeconomic complexities of class and race. Of course we hope that there is a force which is not subject to the banal laws of the world, and that it will come and magically provide us with all the things that we desire most.

Then there will be a moment of disappointment; and we will come to understand that love, as portrayed in this movie, does not exist. Instead we find something better and more real: it is now our responsibility to create the magic, especially for those who do not yet know how to conjure it for themselves. In the complexities of doing so, we may realize what it means to have courage.4

#77

Ok, more than a little dirty. I slipped (on god knows what) and fell and cut my hand on the ground one evening; despite washing my hands for seven hours, I’m still waiting to die of septic shock or all manner of communicable diseases.

And this is a very hard thing to do, because Jeunet is, at the end of the day, an incredibly talented artist, and Audrey Tautou is an amazing actress, and they are some of the finest weavers of romanticism that I have ever seen. Am I guilty of putting the soundtrack on while I eat raclette in my condo in North America? You bet I am.

Also, ok fine this is kind of the best:

And romanticism done right is when someone stares into the ugliness of it all and still chooses to do the work. It’s probably no surprise that Rilke is my favourite example of this:

Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.

[…] if a sadness rises in front of you, larger than any you have ever seen; if an anxiety, like light and cloud-shadows, moves over your hands and over everything you do. You must realize that something is happening to you, that life has not forgotten you, that it holds you in its hand and will not let you fall.

-Letters To A Young Poet

Real courage - of the kind that the Glass Man tells Amélie to have, and that she may yet find:

Voilà, ma petite Amélie, vous n'avez pas des os en verre. Vous pouvez vous cogner à la vie. Si vous laissez passer cette chance, alors avec le temps, c'est votre cœur qui va devenir aussi sec et cassant que mon squelette. Alors, allez-y, nom d'un chien!

(”So, my little Amélie, your bones aren't made of glass. You can take life's knocks. If you let this chance go by, eventually your heart will become as dry and brittle as my skeleton. So... Go and get him, for Pete's sake!")