How DeBeers invented a shortcut to "forever"

Because spending money, however much, is still easier than actually keeping a promise

I’m not much of a jewelry person, but I bought a pair of earrings last week. I did research across a few retailers to ensure that I was simply fueling my vanity, and not, say, a war in Sierra Leone, or rampant carbon emissions and habitat destruction1. The algorithms, merciless against women in their 30s, sunk their teeth into my search history - and now I am being pummeled by ads for diamond engagement rings.

Most people know by now that despite De Beer’s attempts to suggest otherwise, the practice of proposing with a diamond ring is neither traditional nor universal. It was popularized by a series of ad campaigns in the 1940s. By their own admission, the phrase “a diamond is forever2” was coined in 1947 by one Frances Gerety - a woman working at a Philadelphia ad agency on the De Beers account.

This “enduring” tradition has probably existed for less time than you have

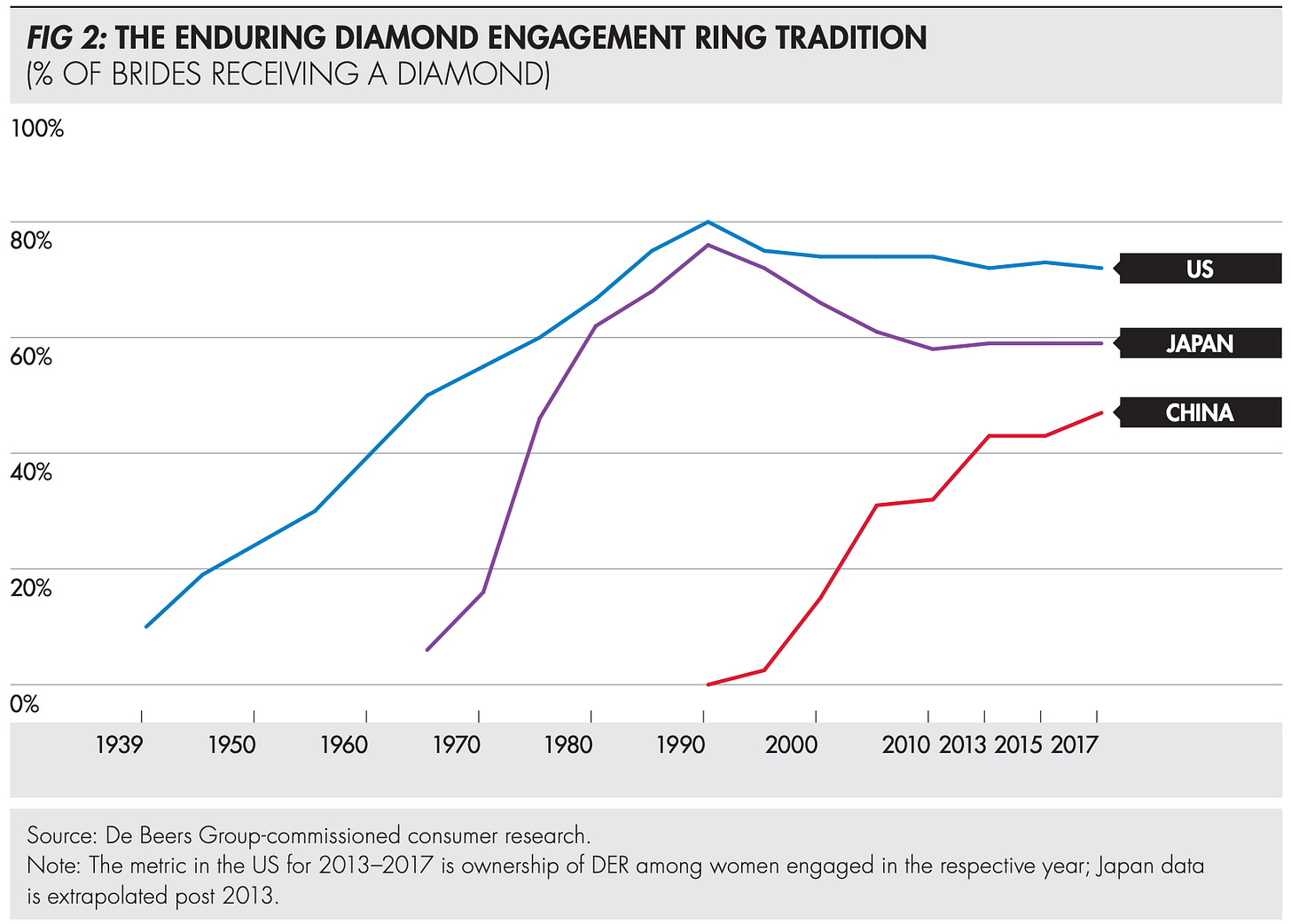

The most commonly quoted statistic, according to De Beers’ own research, is that only 10% of American brides received diamond engagement rings in 1939. This number steadily rose to 80% by 1990. What’s also interesting is that the practice didn’t exist at all in China prior to the 1990s. Its rise coincides squarely with China’s opening to Western capitalist markets and ideas, starting with Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s and reaching full force by the time of the Jiang Zeming era (1990s to early 2000s).

In other words, there is nothing traditional nor timeless about the practice of proposing with a diamond engagement ring3. It is, however, an impressive commercial meme that has spread like wildfire over the last few decades in modern Western markets.

Yet most of us have a healthy skepticism of commercial motives. Nutella has been trying for years to convince us for years, via advertising and packaging, that it is a healthy breakfast food - and nobody is falling for it. So what is it about De Beers’ messaging that has penetrated the American psyche? How is their rhetoric able to manipulate behaviour at the heart of something - love - which is meant to transcend the crass transactionality of our world?

Spending money is easy; relationships are hard

Esther Perel jokes, on Huberman’s podcast, that an honest set of wedding vows might go something like “I will fuck up, and I will occasionally own up to it”. I would add something like “this is going to be terrible, but I promise that after I calm down and no longer feel like punching you in the face, I will give this one more try.”

Intractable edge cases aside (like violence, abuse, or a underlying lack of respect), this should surprise nobody who has actually been in a relationship. The idea that half of marriages fall apart is often used as evidence that our generation has somehow lost the ability to commit. I’m more amazed that half the people who get married are stubborn and masochistic enough to actually deal with each other for a lifetime.4

I think it’s more likely that we’re not quite grokking the absurd nature of that commitment. When examined seriously, it should send any sane human being running for the hills. I will patiently work with your flaws and insecurities…forever?! I will do the emotional labour of pulling myself out of my own perspective to empathize with your point of view? Even (and especially) in the moments when all I want to do is table-flip and say “fuck this noise, I had no idea you were so screwed up”?

That’s a hell of a promise to make. Most of us will spend a lifetime trying to figure out how to do this just a little bit less poorly for our own selves. How can you feel any confidence making that promise to another person? How do you know that you have the capacity to keep it?

All this leads me to conclude that bona-fide “we’re gonna do this shit forever” marriage5 requires one of two things: a Thich-Nhat-Hanh level of self-reflection, emotional skill, and well-adjustedness; or just plain insanity and delusion. Some of the luckier among us may start with the latter, and transition into the former at least a little bit before we die.

Symbols and rituals peddle certainty in a scary world

Esther Perel says that relationships are an act of meaning-making. All symbols and rituals are an act of meaning-making: this is how religions work, and some get so good at it that they can motivate people to kill each other.

I think this goes a long way to explaining why people get so obsessive and existential about engagement rings and wedding dresses. They are symbols for the real thing that we’re after: reassurance that we won’t be left alone to cry in a corner. Attachment is a hell of a beast that even the most well-adjusted of us wrestle with. The fear of loneliness and abandonment begins the moment we are born into this world, and it never quite ends, no matter how deep we push it down into our subconscious. Even the Supreme Court felt the need to comment on it:

Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there.

-Justice Kennedy, in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015)

Except it doesn’t. Marriage doesn’t guarantee anything at all. People (usually) do not burst into flames when they get divorced. On the one hand it is a monumental black hole of symbolic and emotional importance for most people; on the other hand, it’s an entry in a government server rack somewhere which can be deleted, and maybe an expensive party.

Very few people would put their lives in the hands of a surgeon who has a 50% survival rate. Likewise, a promise that is only kept 50% of the time is really no promise at all. And so we search desperately for other signs of authenticity.

Marketing (and religion) has always been a statement of the following form: “if you do x, y will happen”.6 The narrative being sold by De Beers is ultimately this: “someone who will spend this much money on something entirely unnecessary, with no practical function, other than to communicate to you that they love you, must really, really mean it.” The banal act of drinking wine takes on an enormous and strongly defined symbolism when performed in a Christian context. Likewise, the act of gifting an expensive, cut-up rock takes on a defined symbolism when performed in the context of a post-1940s Western relationship. (Most of us just prefer not to think too hard about who defined it).

In many ways, it is easier to spend $x,000 - and to know that it will be understood a certain way - than it is to express how much you love someone. Or, perhaps more accurately, how badly you want someone to love you.

It’s less that De Beers is deliberately bamboozling us, and more that we have always been suckers for any whiff of certainty in this vast and scary world. Religions and governments have always fought incumbent meaning-makers by accusing them of lacking legitimacy or authenticity. Likewise, De Beers’ problem is not the fact that diamonds can now be grown in labs. It’s that their industry is losing control of a powerful narrative.

But the narrative of how to love someone never belonged to anybody in the first place, much less Anglo American PLC. If asked whether you wanted a mining company to officiate your wedding, I imagine that most of us would say no. And yet $300-500 million USD of rough diamond sales per quarter reveals a certain willingness to outsource our cultural narratives about love to an oddly specific and concentrated group of authors.

So a 31% YoY decline in sales is perhaps the most humanist thing that I have seen in a financial statement in a long, long time. Maybe we’re losing interest in other people’s ideas of what this story ought to look like. Maybe we’d like to write it ourselves.

#149

Yes yes mandatory disclaimer that I’m sure there are ethical mined diamonds out there which didn’t kill any rainforests or child soldiers

They are also technically not: a diamond will combust to pure CO2 at 900 degrees Celsius, much like anything else made of carbon.

Yet this is precisely what De Beers tries to suggest in their latest ad campaign to fight the rise of lab-grown diamonds amongst the millennial crowd, by likening them to the “trial by fire” and the long process of polishing and refinement that is an authentic, worthwhile human life.

They seem to have forgotten that lab-grown diamonds, too, are created via insane amounts of heat and pressure and are also cut and polished. The only difference is the deliberate application of engineering ingenuity in order to forgo profound environmental damage, avoid funding murderous regimes, and upend existing markets and social orders.

Is that less emblematic of human self-worth than whatever gets drummed up by the randomness of nature (and the desires of unhappy board members)? I’ll let you decide:

I recently ran a half-marathon and saw a guy holding an extremely accurate and self-aware sign that said “You think this is hard? You should try dating me!”

You could replace the word “marriage” here with “company-founding” or “having children” and it would still apply.

I was once walking with a friend down the street and she kept pointing out that all the women who had partners that she found attractive were blonde. I asked her why this statistically dubious narrative was appealing, given that she wasn’t blonde, and she gave an incredibly self-aware response: “I think I like the idea because it’s an easy answer to the problem.”

One can become blonde and one can expend various amounts of effort and money doing it. You can get a crappy, cheap-looking job in a Chinatown salon for $50, or you can pay thousands for balayage and root upkeep, presumably with a linear increase in quality of boyfriend that shows up as a result.

Likewise you can buy a <cz/moissannite/insert other economical diamond-adjacent substance> or you can feel profound emotional comfort in the idea of paying thousands for something that was pulled out of the ground. The hope is the same: that you’re acquiring a symbol which will lead to a desired outcome, and that the symbol you’re getting is the real deal.