Floristry as architecture

An inquiry into why I am so misogynist about so-called feminine "arts and crafts"

My obsession with houseplants has diverged into a related cousin, which is an obsession with cut flower arrangements. I used to find them stupid and wasteful - why spend $60 on a bouquet that will last two weeks and then die, when you can purchase a Monstera for the same price? I’ve recently relaxed that judgement, with the realization that they are an art form like anything else, and serve about as much purpose as writing a blog post once per week.

Floristry sits at an interesting intersection of art, aesthetics, and femininity. By femininity I mean in stark contrast to traditionally masculine professions like architecture, which enjoy the intellectual of protection being “analytically rigorous” while providing the freedom of subjectivity - and emotionality - that is inherent in the idea of taste.1 In most bookstores, books about flower arranging are almost always shuttered away into a Crafts and Hobbies section, despite the fact that many of them possess language and a level of conceptual hauteur that would make them perfectly at home next to books on Architecture or Art Theory.

If anybody doubts whether this degree of intellectual sophistication can be found in dead plants, I invite you to contemplate these examples of ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement:

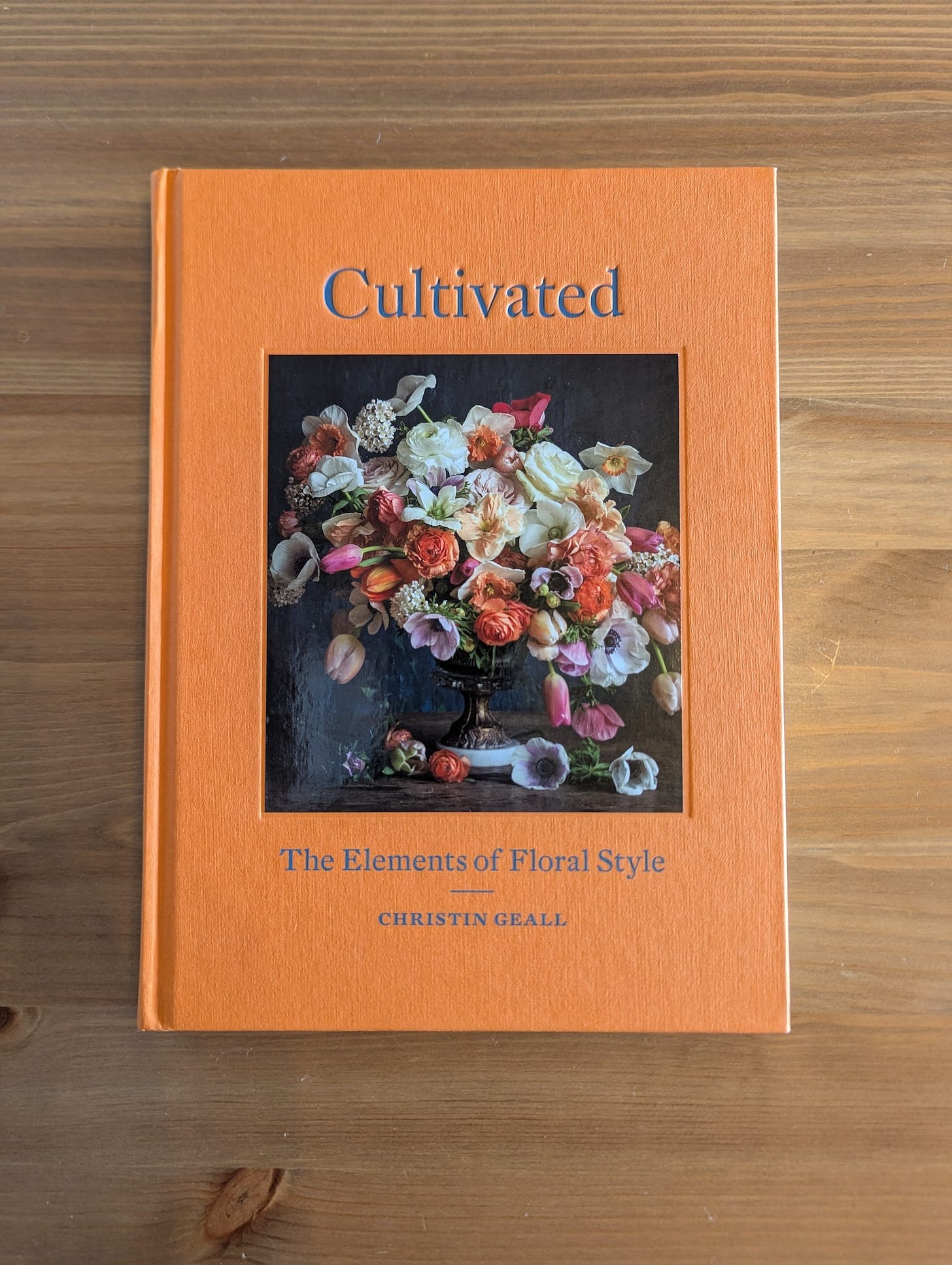

Yet I was still slightly embarrassed the other day when searching for a copy of Cultivated by Christin Geall at Indigo, 1) because it was a Heather’s Pick2; and 2) because it was shelved inches away from books on scrapbooking and friendship bracelets:

I didn’t even realize how much internalized misogyny I had around so-called “women’s” hobbies. When it’s a hobby that tends to find itself over-represented on “live-laugh-love” flavoured mommy-blog Instagram accounts with photoshoots in barns, it’s simply that much worse. (How many florist websites are plastered with cloying cliches about “sharing joy”, or “cherishing life’s special moments?”) Even now I have to reassure myself that it’s ok to like flowers, and to read about how to arrange them nicely, by telling myself that 1) the book was published by The Princeton Architectural Press (and therefore has a certain masculine seal of analytical approval); and 2) that it sits beside the other books that I’ve purchased on botany, which is, thank goodness, a real science3.

This weird misogyny is completely nonsensical, even as I recognize it in myself. In The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo, one of her clients describes the desire to live “a more feminine lifestyle”:

“I’d have a pink bedspread and a white antique-style lamp. Before going to bed, I would have a bath, burn aromatherapy oils, and listen to classical piano or violin while doing yoga and drinking herbal tea. I would fall asleep with a feeling of unhurried spaciousness.”

-p. 37 (“Before you start, visualize your destination”

Marie Kondo, genius as she is, then drops this truth bomb on us:

Your next step is to identify why you want to live like that. Look back over your notes about the kind of lifestyle you want, and think again. Why do you want to do aromatherapy before bed? […] Maybe your answers will be “I don’t want to be tired when I go to work the next day,” […] Ask yourself “Why?” again, for each answer. Repeat this process three to five times for every item.

As you continue to explore the reasons behind your ideal lifestyle, you will come to a simple realization. The whole point in both discarding and keeping things is to be happy.

We can apply this philosophy to arranging cut flowers indoors. Why do it at all? Dig beyond the superficial answer that they are pretty: there is an intricacy to living things that most artificial creations cannot match. (Anybody who has ever looked at a faded, fake flower up close in a cheap restaurant knows what I am talking about.) The problem with bringing a portion of a living thing indoors is that it tends to die.4 Like luxury goods, it is the ephemeral nature and inherent scarcity of cut flowers that makes the thing worth having. To knowingly spend a grocery shop’s worth of of money on something that will be tossed in 2 weeks, with no practical purpose other than to be looked at, is to purchase reassurance that one is not (yet) on the brink of death, and in fact have plenty of life to spare.5

To curate that natural beauty via the act of selecting and arranging is to go one step further. It is deliberate action. It is mindfulness. It is the luxury of spending time and attention on something simply for the sake of creating beauty, and it cannot be accused of having ulterior motives because it is utterly, utterly useless. In that sense, and like all art, it is pure.

And finally, to then ask, “why does this work”, “why do I find this beautiful”, “why do I love this” - that is either insufferable navel-gazing, or the very stuff that makes life worth sticking around for.

You decide.

Week 7 (of my bid to write one essay a week, for the rest of the year.)

It’s almost as if men are not permitted to emote out loud, and must invent things like architecture or the study of ancient Roman arrowheads to sublimate all their pent up life energy into

I, in all my hubris, thought myself above such basicness. It’s a slippery slope from there, isn’t it? What’s next, am I going to start taking picks from Oprah’s Book Club? Or Barack Obama’s favourite summer reads list? Aiya.

On this note, one of my favourite art exhibits that I’ve ever seen at the Tate Britain is called preserve ‘beauty’ by Anya Gallaccio. It consists of thousands of fresh gerberas fixed to a wall and simply…left there:

I’ve heard a similar argument for why cigarettes are considered sexy: that the act of doing this thing that objectively shortens your lifespan is a demonstration of how much life you have to spare. As in, I’m so alive, I can afford to kill myself a little bit.

Love this article! Another joy I have found in having indoor flower arrangements is, because they are alive and also dying, they are constantly changing. I realized one day that a dying living thing can be extremely beautiful. The plus side of the natural aging process.