Why art is the loneliest way to connect

The dishonesty of yearning for connection, but going about it in this roundabout fashion

Preamble: having fallen off the writing bandwagon this year, I am once again setting an arbitrary goal with no justification or purpose, to hold myself accountable to nobody in particular: one essay a week, from now to the end of the year. This is #1.

On a recent episode of Call Her Daddy, Halsey makes the observation that a lot of people in her line of work (entertainment) do it out of a desire to be seen, usually due to a lack of connection in childhood. What’s ironic is that most people, when asked about the art that they like, will cite the fact that it’s relatable. What they find compelling is not the glamorous stage persona or the reality that this celebrity’s life is very different from theirs: what they find compelling is the ways in which they are similar.

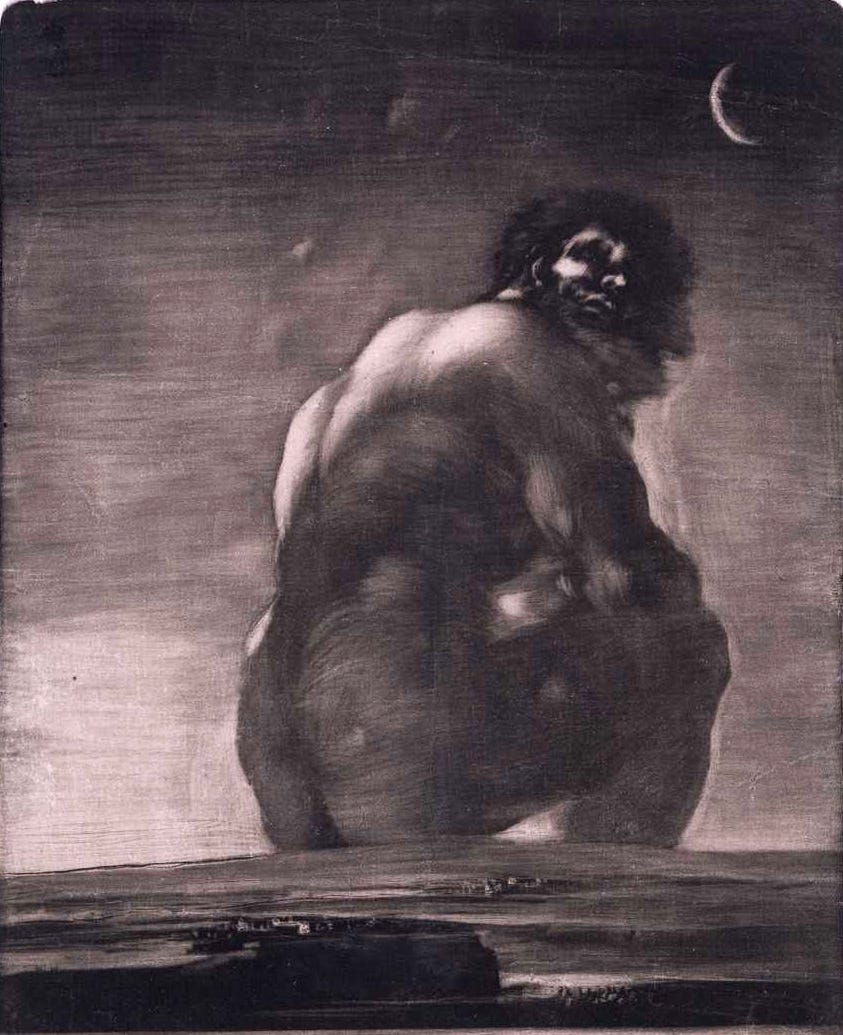

The irony, of course, is that some of the most popular songs, paintings, stories, and movies, surrounded by the biggest throngs of adoring fans, are about feeling lonely, disconnected, unloved, small, and unimportant. Apparently we were all awkward loners in high school:

The young officials laughed at and made fun of him, so far as their official wit permitted[…] But Akakiy Akakievitch answered not a word, any more than if there had been no one there besides himself. It even had no effect upon his work: amid all these annoyances he never made a single mistake in a letter. But if the joking became wholly unbearable, as when they jogged his hand and prevented his attending to his work, he would exclaim, “Leave me alone! Why do you insult me?” And there was something strange in the words and the voice in which they were uttered.

-The Overcoat, by Nikolai Gogol

Frank O’Connor claims that this is the brilliance of The Overcoat:

There the story ends, and when one forgets all that came after it, like Chekhov's "Death of a Civil Servant," one realizes that it is like nothing in the world of literature before it. It uses the old rhetorical device of the mock-heroic, but uses it to create a new form that is neither satiric nor heroic, but something in between-something that perhaps finally transcends both. So far as I know, it is the first appearance in fiction of the Little Man, which may define what I mean by the short story better than any terms I may later use about it. Everything about Akakey Akakeivitch, from his absurd name to his absurd job, is on the same level of mediocrity, and yet his absurdity is somehow transfigured by Gogol.

-from The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story by Frank O’Connor

Which explains, I suppose, why we are so susceptible to some famous person on a stage, laying bare the fact that they have the same existential thrashings as us little people:

What Gogol has done so boldly and brilliantly is to take the mock-heroic character, the absurd little copying clerk, and impose his image over that of the crucified Jesus, so that even while we laugh we are filled with horror at the resemblance.

It’s easy to accuse Christianity of being the opiate of the masses. Look at all these poor, miserable people, clinging desperately to the idea that they are simultaneously flawed and wretched, yet somehow still infinitely deserving of love! What fools.

But secular society is full of the same hypocrisy. Replace “poor and miserable” with “mediocre and unremarkable”, and “infinitely deserving of love” with “still worthy of attention anyway”, and that might explain why decently well-paid lawyers and software engineers with mortgages in good school districts will go do things like sign up for pole-dancing classes, or fiction-writing workshops, all in the name of “expressing themselves”. The cry for attention over our banal, unremarkable lives is downright cringe-worthy, so we need the veneer of legitimacy and sophistication that art provides. Wailing over the guy who just broke up with you is pathetic, unless you win a Grammy for it. Navel-gazing is unbecoming, unless it’s in the Tate Modern. Writing stories about the experience of being an awkward loser is generally considered a weird, angsty teenage thing that you ought to have grown out of by now, unless you happen to be Gogol, in which case Turgenev and O’Connor will immortalize you for all time:

"We all came out from under Gogol's 'Overcoat'" is a familiar saying of Turgenev, and though it applies to Russian rather than European fiction, it has also a general truth.

Yet anybody who has even vaguely artistic friends knows that they are usually the fucking worst. If they had the ability to relate well to others, they wouldn’t be doing all this roundabout “please-look-at-my-sadness” nonsense. My therapist made the astute observation that I enjoy writing because it provides a way of feeling connected to other human beings, which is something that I crave deeply. What she was too kind to add was “and if you had other effective ways to do this, you’d be doing that instead of writing into a void on the Internet”.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in a room full of students taking a creative writing course. There is a fantastic dissonance in watching a dozen individuals discuss, in great emotional depth, the metaphors for social isolation in a short story, and then completely ignoring each other at break time - or better yet, falling into familiar and comfortable cliques along self-revealed professional backgrounds and political values. Throw in the usual amount of jockeying over who can string together the most eloquent sentences, or expound the most sophisticated political opinions, and you start to feel that regular old social alienation would be downright preferable to hanging out with “artists”. At least normal people are honest! E. M. Forster’s famous line from Howard’s End, “Only connect!”, is cited in pretty much every book about literary craft. You’d think writers would be better at connecting than anyone else, but it just ain’t so. It’s easy enough to forget that reading or writing about the thoughts of dead/fictional humans is not the same thing as connecting to actual humans. It’s easy enough to mistake an investment in literary fluency - and neuroticism - for actual emotional development.

Someone in the class said that they preferred the safety of fiction to the messiness of their own lives. This may be the most empathetic, least misanthropic explanation for this weird disconnect that masquerades as artistic depth. The version of “humanity” that shows up in art is less threatening, no matter how sophisticated it is, precisely because they aren’t real. It’s therefore a safer place to start. And a start, no matter how feeble, is perhaps better than nothing at all.

Week 1